Research performed on the International Space Station shows prolonged time in space can cause temporary, and sometimes permanent, blindness, said Julie Robinson, the chief scientist of the International Space Station.

“One of the things we discovered in the last 10 years is that some astronauts, when they go into space, actually have vision loss. A few of those astronauts have permanent vision loss that isn’t reversed when they turn to Earth.”

At first, scientists thought it was a minor issue, but not anymore.

“We thought it was reversible,” Robinson said. “We just didn’t realize that it was a real problem until we started having enough experience on the space station, since it doesn’t happen in everybody.

“We had a few crew members coming home with such significant vision loss that people realized that it wasn’t normal,” Robinson said. “And then we started looking into those, doing extra imaging, some spinal taps on astronauts, and found out they had really high spinal pressures and we realized there was something going on here that really mattered.”

Dr. Steven Laurie, the lead scientist for Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome research says, “We have known since astronauts flew short-duration Space Shuttle missions that vision changes during spaceflight. However, once we started seeing swelling at the back of the eye surrounding the optic nerve, this became more concerning because it has the potential to lead to long-term changes in vision that cannot be fixed with new prescription lenses.”

On July 12, 2012 NASA published a report on the effect of space travel on the vison of astronauts. It was titled “Risk of Spaceflight-Induced Intracranial Hypertension and Vision Alterations”.

Here is an excerpt from the NASA document:

Over the last 40 years there have been reports of visual acuity impairments associated with spaceflight through testing and anecdotal reports. Until recently, these changes were thought to be transient, but a comparison of pre and postflight ocular measures have identified a potential risk of permanent visual changes as a result of microgravity exposure.

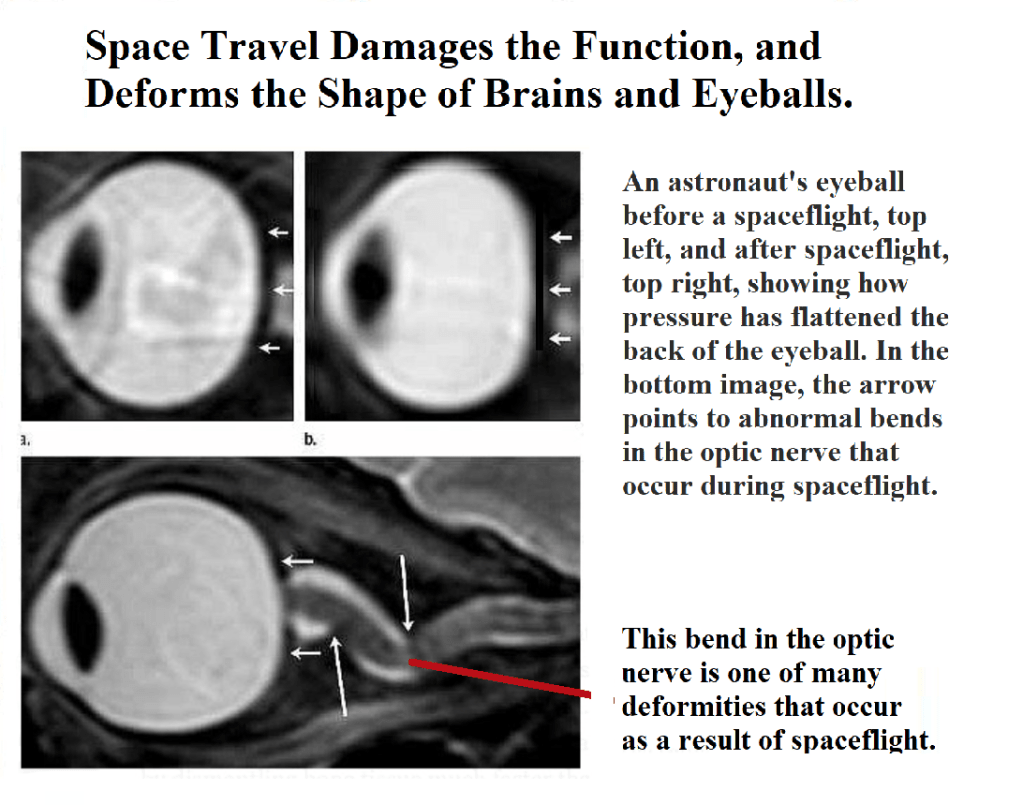

It is thought that the ocular structural and optic nerve changes are caused by events precipitated by the cephalad-fluid shift crewmembers experience during long-duration spaceflight.

To date, fifteen long-duration crewmembers have experienced in-flight and postflight visual and anatomical changes including optic-disc edema, globe flattening, choroidal folds, and hyperopic shifts as well as documented postflight elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). In the postflight time period, some individuals have experienced transient changes while others have experienced changes that are persisting with varying degrees of severity.

NASA has determined that the first documented case of a U.S. astronaut affected by the VIIP syndrome occurred in an astronaut during a long-duration International Space Station (ISS) mission. The astronaut noticed a marked decrease in near-visual acuity throughout the mission. This individual’s postflight fundoscopic examination and fluorescence angiography revealed choroidal folds inferior to the optic disc and a cotton-wool spot in the right eye, with no evidence of optic-disc edema in either eye. The left eye examination was normal. The acquired choroidal folds gradually improved but were still present 3 years postflight.

Additional cases of altered visual acuity have been reported since, and one case has included the report of a scotoma (visual field defect), which resulted in the astronaut having to tilt his head 15 degrees to view instruments and procedures. These visual symptoms persisted for over 12 months after flight. This type of functional deficit is not only of concern to the individual, but is of concern to the mission and the ISS program managers.

Changes in visual acuity are not uncommon in astronauts, although there appears to be a higher prevalence among long-duration crewmembers. Specifically, 29% of short-duration and 60% of long-duration crewmembers reported degradation of long distance or near-visual acuity, which in some long-duration cases did not resolve in the years after the mission.

Mader et al. provided a review of seven of the fifteen documented cases reported of male astronauts, who have experienced in-flight visual changes. Since Mader’s publication, a review of data has identified eight additional cases, although some are identified with less precise detection methods. The seven cases described by Mader correspond to astronauts who spent 6 months on board the ISS. The ophthalmic findings consisted of disc edema in five cases, globe flattening in five (all of which demonstrated optic sheath distention), choroidal folds in five, ‘cotton-wool spots’ in three, nerve fiber layer thickening detected by OCT in six, and decreased near vision in seven astronauts. Five out of seven cases with near vision complaints had a hyperopic shift of 0.50 D cycloplegic refractive change or more between pre and post-mission. Some of these refractive changes remain unresolved years after flight. While the etiology remains unknown, it is proposed that these findings may represent manifestations of a pathologic process related to (but not limited to) the eye and the optic nerve, the brain, and the vascular system (venous congestion in the brain and the eye orbit), in concert with intracranial effects caused by cephalad-fluid shifts experienced during microgravity exposure.